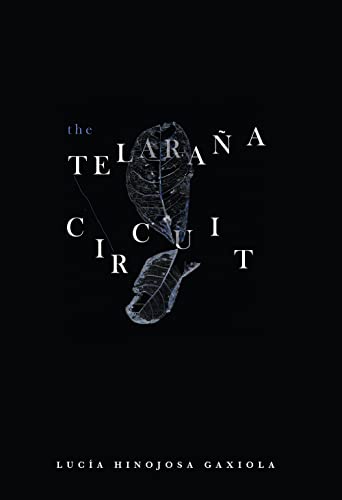

The Telaraña Circuit by Lucía Hinojosa Gaxiola

The Archive Is Breathing

Is memory a place we visit, or a thing we build? A new generation of poets argues it’s neither. It’s a network we inhabit.

We are living in an age of total recall and digital amnesia. Our lives are meticulously documented, our every gesture captured, tagged, and stored in a server cloud. Yet this relentless accumulation of data has done little to satisfy our hunger for memory. In fact, it may have exacerbated the crisis. The digital archive is inert; it is a tomb, not a territory. It holds files, but no feeling. This friction—between the dead data we store and the living past we crave—has become a central anxiety of our time. We are desperate to know how to make the archive breathe.

Into this cultural impasse steps a new wave of “archival poetics,” a movement less concerned with recounting the past than with reactivating it. These poets are not historians; they are part sorcerers, part archaeologists, using the text as a site of excavation. They sift through the fragments of the past—photographs, letters, state documents, family lore—to find a pulse. And perhaps no debut collection better embodies the power and potential of this project than Lucía Hinojosa Gaxiola’s The Telaraña Circuit. This is not a book about memory. It is a “sustained investigative thought-web,” a multimedia, bilingual, and radically open work that attempts to build a living circuit, a telaraña (spider’s web), where the past and present can touch, vibrate, and transmit energy.

Gaxiola’s central ambition is to redefine the act of remembrance itself—to move it from a passive, nostalgic gaze to a “meticulous, sensuous act of unearthing.” The book’s project is ignited by a personal inheritance: the archive of her late aunt, an archaeologist. Gaxiola, in turn, becomes an archaeologist of her aunt’s archive, and in doing so, provides a stunning blueprint for a poetics of “haptic process.” This is a book that asks: What if “listening” was a tactile act? What if we could feel the “ecology of sound”? What does the past feel like, and how can the page be engineered to carry that sensation?

This is Gaxiola’s first full-length collection, and it arrives with the formal confidence and intellectual rigor of a mid-career masterpiece. It places her immediately in conversation with contemporary innovators like M. NourbeSe Philip or Anne Carson, who treat the page as a visual and acoustic field, as well as with the process-based work of predecessors like Susan Howe. But where Howe excavates the library, Gaxiola excavates the earth, the body, and the family photograph. Her work is part of a thrilling cohort of Latinx artists and writers—like Mónica de la Torre or the late C.D. Wright—who are charting the borderlands between text and image, body and landscape, Spanish and English.

The book defies simple summary because it is not a linear collection. It is a “process book,” a layered “mesh of charged, fractal elements” that must be experienced rather than merely read. Gaxiola, a “connoisseur of the fragment,” presents us with a dazzling and disorienting array of materials: haunting video stills of hands in motion, handwritten notes that drift across the page, drawn symbols, old family photographs, and typewritten poems that are as much visual objects as they are linguistic ones.

Take a poem that unfolds from a “video still.” The text might describe a gesture, while the image itself is present on the facing page, and a bilingual annotation in the margin questions the “materiality of language” itself. Gaxiola “expertly weaves sound, image, and word” until they become indistinguishable. She is not simply decorating her poems with images; she is insisting that the image is the poem, that the handwritten scrawl is the thought, that the “residual trace” of a performance is the event itself.

In one section, she overlays her aunt’s archaeological field notes with her own poetic “fieldwork.” The effect is electric. The two “excavations”—one scientific and historical, the other artistic and personal—begin to resonate. The “unearthing” of a pre-Columbian artifact and the “unearthing” of a personal memory are shown to be part of the same haptic investigation, the same “curious listening.” Gaxiola’s formal choices force this connection. By placing these fragments side-by-side, she creates a circuit. The “vibratory aspect” of one fragment triggers a resonance in the other. This is Gaxiola’s “telaraña” in action. The book doesn’t just tell us about this connection; it makes us, the reader, the nodal point who feels the web tremble.

And yet, for all its brilliant conceptual machinery, can the circuit always carry the current? A project this committed to “process” over “product” necessarily runs the risk of keeping its reader at an intellectual remove. Gaxiola’s devotion to the “residual trace” and the “fragment” is the book’s greatest strength, but it is also the source of its one, significant limitation. There are moments in this collection where the investigation feels too rigorous, where the academic and conceptual scaffolding is so visible that it blocks the emotional light.

In its quest to be a “multimodal” artifact, a few pieces feel more like exhibits in a “process” archive than fully realized poems. The reader can admire the “gift for the visual molecular embodiment” of the idea without ever being moved by it. This is the inherent paradox of archival poetics: in the meticulous “unearthing” of the past, one can sometimes forget to breathe life into it. The book’s overwhelming praise from experimental circles is well-deserved, but a reader looking for a more conventional, sustained emotional core to anchor them in this disorienting web may occasionally feel lost. The “haptic process” is fascinating, but at times, one longs for the simple touch of a hand.

This limitation, however, feels less like a failure than a necessary by-product of the book’s profound ambition. Gaxiola has not set out to write a tidy collection of lyrical poems about her family. She has set out to build a machine for re-enchanting the archive. And in this, she overwhelmingly succeeds.

The Telaraña Circuit is a landmark debut. It does not resolve the anxiety of our age of dead data, but it offers a powerful antidote. It reminds us that memory is not a file to be opened. It is a “radically open” field to be entered, a “layering” of textures to be felt. Lucía Hinojosa Gaxiola has given us a book that is “alive,” a book that teaches us how to listen, not just with our ears, but with our eyes and our skin. It demands that we become active participants, that we “synchronize [our] breath to the rhythms of its ongoing motion.” It is a demanding, brilliant, and necessary work that does not let us forget that the past is never truly past; it is vibrating, right beneath the surface, waiting for us to listen.